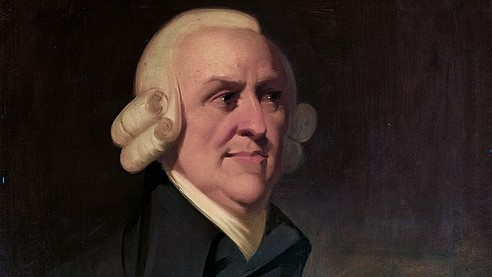

Adam Smith (1723-1790): Life, Work, and Human Nature

Born on June 5, 1723, in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, Adam Smith is best known for his transformative contributions to economics and moral philosophy. His two seminal works, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments” (1759) and “The Wealth of Nations” (1776), provide deep insights into his views on human nature and the recipe for a good life, while setting the foundation for modern economic theory.

Smith’s intellectual journey began at the University of Glasgow, where he studied under the eminent philosopher Francis Hutcheson. Afterward, he attended Balliol College, Oxford, but found its academic environment stifling. He returned to Scotland and delivered public lectures in Edinburgh before rejoining the University of Glasgow as a professor in 1751.

In “The Theory of Moral Sentiments,” Smith explored morality’s foundation in human nature. He proposed that sympathy, or the ability to imaginatively assume another’s feelings, is the basis of moral judgment. Smith maintained that virtue is the path to a contented life; he identified prudence, justice, and beneficence as the chief virtues. His philosophy, deeply humanistic, stressed the importance of virtues in economic transactions, too.

Smith practiced what he preached, with anecdotes from his life illustrating his adherence to these virtues. For instance, he was known for his generosity, often assisting students financially and providing free lectures to those who couldn’t afford them. This exemplified his belief in beneficence, defined as doing good to others. He was also known for his fair treatment of others, mirroring his emphasis on justice. His prudent lifestyle was evident in his modest living and prudent management of his finances, enabling him to donate to charitable causes.

In 1776, Smith published his groundbreaking work, “The Wealth of Nations,” revolutionizing economic thought. Smith posited that the wealth of a nation lay not in its accumulation of gold but in its productive labor. He advocated for a laissez-faire economy, where individual self-interest, guided by an ‘invisible hand,’ would lead to societal prosperity. However, he acknowledged the necessity of certain regulations to protect society’s weakest members, again reflecting his belief in justice and beneficence.

Smith’s views on human nature and the good life influenced his economic philosophy. He saw wealth not as an end but as a means to ensure the well-being of all society members. He suggested that economic prosperity arises from a society where individuals are free to pursue their interests, provided they do so justly and with consideration for others.

Reception and Influence

Smith’s work has elicited responses from various philosophers and scientists. Karl Marx, the father of communism, acknowledged Smith’s influence while critiquing his view of labor value. Marx contended that labor isn’t free in a capitalist society, as Smith suggested, but is exploited.

Meanwhile, John Maynard Keynes, the influential economist, admired Smith’s work but believed that government intervention was necessary to stabilize economies, contradicting Smith’s laissez-faire ideology.

Philosopher Amartya Sen highlighted the often-overlooked moral elements in Smith’s economic thought. Sen emphasized Smith’s belief in the necessity of basic welfare for all members of society, not just the pursuit of individual wealth.

In the realm of psychology, Steven Pinker referenced Smith’s ‘impartial spectator’ theory in his exploration of human moral intuition. Smith’s idea that we judge our own actions as if observed by an impartial outsider resonates with modern theories of moral cognition.

In recent years, scholars have sought to reclaim Smith from the image of a one-dimensional champion of free markets, emphasizing his nuanced understanding of human nature and morality. His belief in sympathy, justice, and beneficence as critical components of a well-functioning society continues to inspire contemporary discourse on ethics and economics.

Renowned economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek drew from Smith’s notion of spontaneous order and the ‘invisible hand,’ arguing that markets can organize themselves without central planning. Hayek, however, expanded on Smith’s work to defend a more laissez-faire approach than Smith himself might have endorsed.

The biologist and theorist Richard Dawkins referenced Smith’s concept of the ‘invisible hand’ in his seminal work, “The Selfish Gene,” to explain how seemingly altruistic behavior can evolve in a population of self-interested individuals. In doing so, Dawkins illustrated the broad applicability of Smith’s insights beyond economics into the realm of evolutionary biology.

Despite the diversity of these responses, there is a common acknowledgement of Smith’s profound influence. His groundbreaking ideas have not only shaped the discipline of economics but also significantly impacted philosophy, psychology, and even biology.

Adam Smith’s life and work represent a remarkable blend of philosophy and economics, grounded in a deep understanding of human nature. His vision of the good life, based on the virtues of prudence, justice, and beneficence, shaped his economic theories and continues to inspire contemporary thought. His belief in the inherent capacity of humans for sympathy and moral judgment provides a humane underpinning to his economic doctrines. This understanding of Smith, as both an economic theorist and a moral philosopher, offers a more nuanced appreciation of his contributions and their lasting influence.

Bibliography

- Smith, Adam. “The Theory of Moral Sentiments.” London: A. Millar, 1759.

- Smith, Adam. “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.” London: W. Strahan; and T. Cadell, 1776.

- Evensky, Jerry. “Adam Smith’s Moral Philosophy: A Historical and Contemporary Perspective on Markets, Law, Ethics, and Culture.” Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Fleischacker, Samuel. “On Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations: A Philosophical Companion.” Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Hayek, Friedrich. “Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 2: The Mirage of Social Justice.” University of Chicago Press, 1976.

- Marx, Karl. “Capital, Volume I.” Penguin, 1867/1990.

- Keynes, John Maynard. “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.” Macmillan, 1936.

- Sen, Amartya. “The Idea of Justice.” Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Pinker, Steven. “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined.” Viking, 2011.

- Dawkins, Richard. “The Selfish Gene.” Oxford University Press, 1976.

- Phillips, Ronnie. “The Chicago School and the History of Economics.” History of Political Economy, 1983.

- Berry, Christopher J. “The Idea of Commercial Society in the Scottish Enlightenment.” Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

Please note that this bibliography consists of a mix of primary sources (works by Adam Smith) and secondary literature (scholarly works about Smith’s ideas).