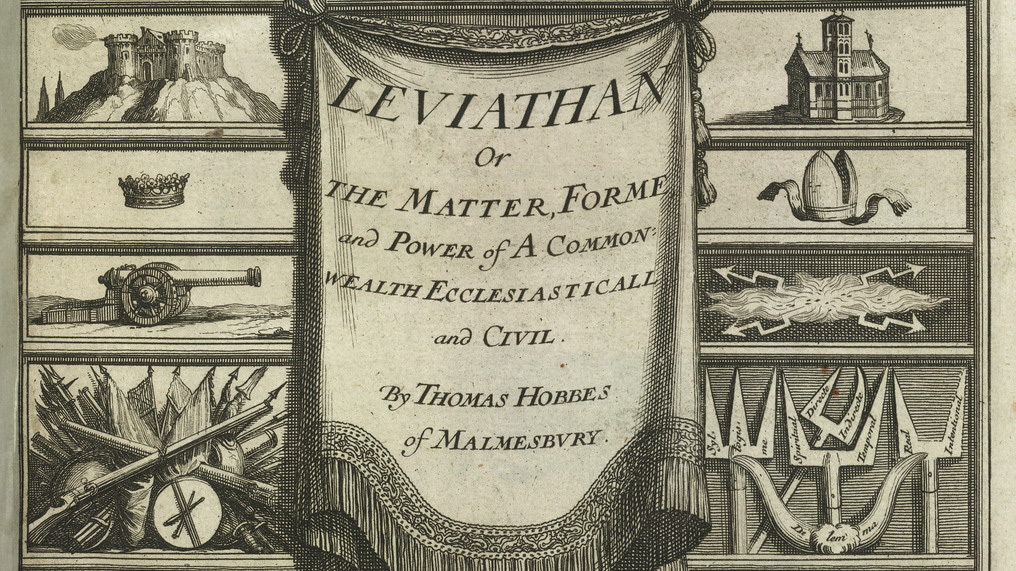

Leviathan is a political treatise written by the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes and published in 1651. It is one of the most influential works of political philosophy in the Western tradition and is regarded as a cornerstone of modern political theory.

In Leviathan, Hobbes argues that the natural state of humanity is one of constant war and conflict, where life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” To escape this state of nature, individuals must surrender their rights to a sovereign ruler, who can maintain order and protect them from violence. According to Hobbes, this social contract is necessary for the survival and prosperity of society.

The title of the book, Leviathan, refers to a sea monster from the Bible, symbolizing the power and authority of the sovereign ruler. Hobbes argues that the Leviathan must be given absolute power in order to maintain order, and that any rebellion or dissent against the ruler is a threat to the stability of the state.

Leviathan is divided into four parts: “Of Man,” “Of Commonwealth,” “Of a Christian Commonwealth,” and “Of the Kingdom of Darkness.” In these sections, Hobbes discusses the nature of man and society, the role of the sovereign, the relationship between religion and politics, and the dangers of civil war and rebellion.

The ideas presented in Leviathan were controversial in Hobbes’s time and continue to be debated by political philosophers today. While some argue that Hobbes’s emphasis on the importance of a strong central government is necessary for maintaining social order, others criticize his authoritarianism and argue that individual liberties should be protected even in times of crisis. Despite these debates, Leviathan remains a foundational text in political theory and continues to shape modern discussions of power, authority, and the role of the state.

Hobbes presents a particular view of human nature, which he describes as inherently self-interested and driven by a desire for power and self-preservation. According to Hobbes, humans are in a constant state of competition with one another, leading to conflict and violence. He argues that this state of nature is a “war of all against all” and that it is only through the establishment of a strong central government that people can escape this state and achieve a stable society.

Hobbes’s view of human nature is thus quite different from that of many other philosophers, who often stress the importance of virtue, moral behavior, and the pursuit of the common good. Hobbes does not deny the existence of morality, but he argues that it is ultimately derived from self-interest and the desire for social order.

In terms of how to live a good life, Hobbes’s emphasis is on obedience to the laws and institutions of the state. He argues that individuals should be willing to surrender their own desires and interests to the greater good of the community, as embodied in the authority of the sovereign. By doing so, people can achieve a measure of security and stability, which is necessary for human flourishing.

Hobbes’s view of human nature and the good life is highly skeptical of the potential for individuals to act morally or altruistically on their own. Instead, he sees the state as the primary means for ensuring peace and prosperity, and individuals as needing to submit to its authority in order to live a good life.

Quotes

On Human Nature:

- “The life of man [is] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” (Part I, Chapter 13)

- “During the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war.” (Part I, Chapter 13)

- “Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of war, where every man is enemy to every man, the same is consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them withal.” (Part I, Chapter 13)

- “For such is the nature of man, that howsoever they may acknowledge many others to be more witty, or more eloquent, or more learned; yet they will hardly believe there be many so wise as themselves.” (Part I, Chapter 13)

- “The passions that incline men to peace, are fear of death; desire of such things as are necessary to commodious living; and a hope by their industry to obtain them.” (Part I, Chapter 13)

On the State and Sovereignty:

- “For as amongst masterless men, there is perpetual war, of every man against his neighbour; no inheritance to transmit to the son, nor to expect from the father; no propriety of goods or lands; no security; but a full and absolute liberty in every particular man: so in states and commonwealths not dependent on one another, every commonwealth (not every man) has an absolute liberty, to do what it shall judge (that is to say, what that man, or assembly that representeth it, shall judge) most conducing to their benefit.” (Part II, Chapter 17)

- “A commonwealth is said to be instituted, when a multitude of men do agree, and covenant, every one, with every one, that to whatsoever man, or assembly of men, shall be given by the major part, the right to present the person of them all, that is to say, to be their representative; every one, as well he that voted for it, as he that voted against it, shall authorize all the actions and judgements of that man, or assembly of men, in the same manner as if they were his own, to the end, to live peaceably amongst themselves, and be protected against other men.” (Part II, Chapter 17)

- “The final cause, end, or design of men… when they enter into society, is the preservation of their property.” (Part II, Chapter 17)

- “The power of a commonwealth, is the power of the sovereign only.” (Part II, Chapter 19)

- “The right of bearing public office, is derived from the gift of the sovereign power.” (Part II, Chapter 21)

On Law and Justice:

- “Justice… is the constant will of giving to every man his own.” (Part III, Chapter 27)

- “The laws of nature are immutable and eternal; and not obliging, as some men have falsely taught, because they are commanded by God Almighty, that can do what he will; nor because they were first published by wise men, that might thereby have an eye to their own ease; but because they were dictated by the nature of man, and therefore are called laws of nature.” (Part III, Chapter 31)

- “The law is a dictate of reason, and therefore not unlike the law of nature; but the law of nature being written in the heart, men cannot read it until they have learned to read by the light of reason.” (Part III, Chapter 31) 14. “The laws of nature are the moral virtues, and their contrary vices, by which in many cases the commonwealth may be both upheld and erected.” (Part III, Chapter 31)

- “The source of every just and unjust action, is not the law of nature, nor the law of nations, but the civil law.” (Part III, Chapter 31)

On Religion:

- “Fear of power invisible, feigned by the mind, or imagined from tales publicly allowed, and thereby made religious, terrifieth inexpert men, and hath been by such feared, not only in the dark, but also in the light, by those that had some phantasm, or imagination of the power of spirits, above their own.” (Part I, Chapter 12)

- “There is no other way of knowing any man’s thoughts but by his words or actions.” (Part II, Chapter 27)

- “The true doctrine of the law of nature is the true moral philosophy.” (Part III, Chapter 31)

- “The kingdom of God by nature cannot be entered into by any that is in the condition of a subject.” (Part III, Chapter 32)

- “The scriptures teach not the doctrine of the natural kingdom of God, but only of the prophetical, which was the same with a Christian commonwealth.” (Part III, Chapter 32)

On Power and Authority:

- “The power of a man is his present means, to obtain some future apparent good.” (Part I, Chapter 11)

- “The power of the mighty hath no foundation in nature; but in the opinion and consent of men.” (Part I, Chapter 13)

- “The only way to erect such a common power, as may be able to defend them from the invasion of foreigners, and the injuries of one another, and thereby to secure them in such sort, as that by their own industry, and by the fruits of the earth, they may nourish themselves and live contentedly, is to confer all their power and strength upon one man, or upon one assembly of men.” (Part II, Chapter 17)

- “The right of nature, which writers commonly call jus naturale, is the liberty each man hath, to use his own power, as he will himself, for the preservation of his own nature; that is to say, of his own life; and consequently, of doing anything which, in his own judgement and reason, he shall conceive to be the aptest means thereunto.” (Part II, Chapter 21)

- “All sovereign power is originally in the people; and none can exercise any part of it, but by their authority.” (Part II, Chapter 26)

On War and Peace:

- “The only way to erect such a common power, as may be able to defend them from the invasion of foreigners, and the injuries of one another, and thereby to secure them in such sort, as that by their own industry, and by the fruits of the earth, they may nourish themselves and live contentedly, is to confer all their power and strength upon one man, or upon one assembly of men.” (Part II, Chapter 17)

- “The passion of war is almost in all men so immoderate, that they delight in it, either by reason of the pleasure they find in exercise of their power, or of their success.” (Part II, Chapter 28)

- “Covenants without the sword, are but words, and of no strength to secure a man at all.” (Part III, Chapter 17)

- “He who carries a sword in public, without any lawful authority, does it not as a citizen, but as an enemy.” (Part III, Chapter 17)

- “In a state of nature, where there is no common power, it is not the strength of the individual, but rather the united strength of the multitude, that counts.” (Part II, Chapter 17)