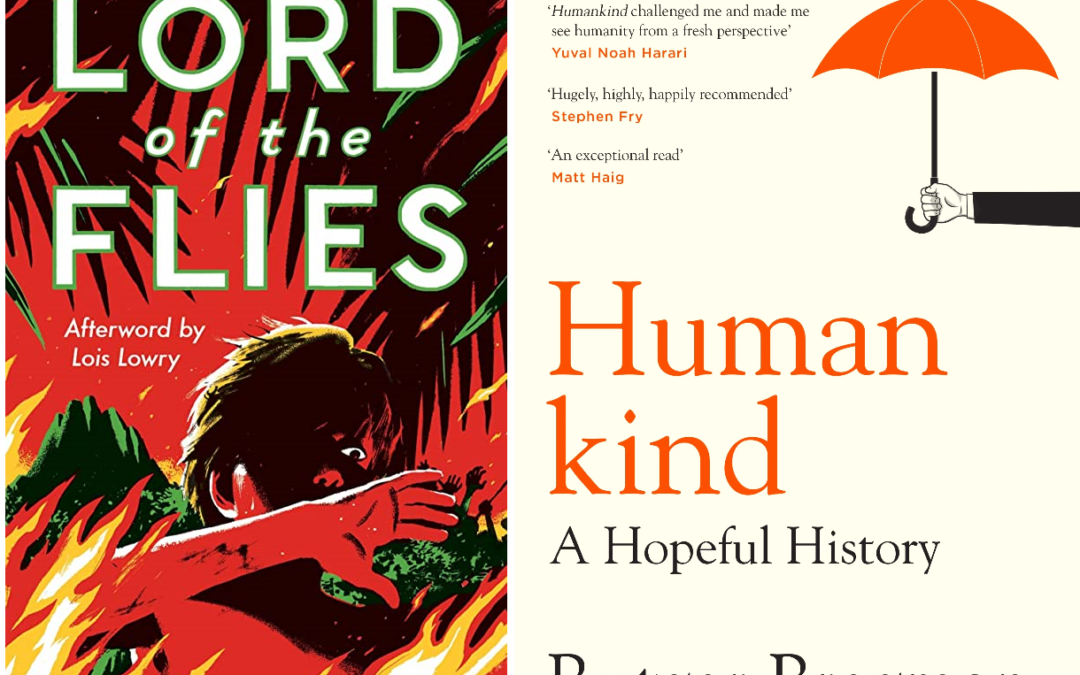

Chapter 2 of “Humankind: A Hopeful History” by Rutger Bregman, translated from Dutch by Elizabeth Manton and Erica Moore, explores the real-life events that challenge the narrative presented in William Golding’s novel “Lord of the Flies.” Bregman sets out to investigate whether children left on a deserted island would actually descend into savagery and chaos, as depicted in Golding’s book. The chapter recounts the remarkable story of six Tongan boys who were shipwrecked on an uninhabited island in 1965 and their subsequent survival.

In Golding’s fictional story, a group of British schoolboys, stranded on a deserted island, quickly descends into chaos and violence. However, the real-life events that Bregman uncovers present a different picture. The Tongan boys, aged 13 to 16, from St. Andrew’s boarding school in Nuku’alofa, found themselves marooned on ‘Ata Island after attempting to sail to Fiji without a map or compass. Unlike the boys in Lord of the Flies, they had no intentions of establishing a hierarchy or engaging in violent behavior.

These boys, instead of turning against each other, formed a tight-knit community. They worked together to survive, creating a sustainable system with a food garden, rainwater storage, a gymnasium, and even a badminton court. They took turns in various responsibilities, such as gardening, cooking, and guarding. Whenever conflicts arose, they implemented a time-out system and encouraged apologies to maintain their friendship.

Their days began and ended with songs and prayers, providing a sense of unity and hope. They endured significant challenges, including a lack of rainfall and a severe storm that destroyed their shelter. One of the boys broke his leg in an accident, but his companions cared for him and set the bone using sticks and leaves. Their resourcefulness, resilience, and cooperation were remarkable.

After being stranded for over a year, the boys were eventually rescued and returned to their families. The community celebrated their return, considering it a miraculous survival story. However, upon their arrival, the boys were unexpectedly arrested and jailed due to legal complications with the boat they had borrowed. Captain Peter Warner, the man who rescued them, came up with a plan to showcase their story as a movie, leading to their release from prison.

The Tongan boys’ tale was transformed into a documentary by an Australian TV crew. The documentary, though plagued with technical difficulties and limited footage, captured the essence of their survival on the island. While their story faded into obscurity, William Golding’s fictional Lord of the Flies continued to be widely read and shaped public perceptions about human nature.

Bregman raises an important point about the impact of storytelling and media. Reality shows like Survivor and Big Brother have perpetuated the idea that people become beasts when left to their own devices. However, the real-life Lord of the Flies challenges this notion. It showcases the power of friendship, loyalty, and cooperation among the stranded boys.

Bregman emphasizes the need to tell different kinds of stories that highlight the positive aspects of human nature. By sharing the remarkable survival story of the Tongan boys, Bregman aims to counteract the negative narratives often perpetuated in popular culture. He argues that stories have the potential to shape our behavior and attitudes, and it is essential to focus on the good and positive in people.

Thomas Hobbes, a prominent philosopher of the 17th century, held a pessimistic view of human nature. According to Hobbes, in the absence of strong governance, humans are driven by their individual self-interests and are prone to a state of war, where life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” He believed that without a powerful authority to control and regulate human behavior, society would descend into chaos.

Given Hobbes’ perspective, it is likely that he would be skeptical of the account of the Tongan boys’ survival on the deserted island. He might argue that their cooperative behavior was an exception rather than the norm, and that such behavior would not be sustainable in a larger or more complex society. Hobbes would likely point out that without a central authority and social contract to enforce order, conflicts of interest and power struggles would inevitably emerge, leading to violence and instability.

Other philosophers who share a similar pessimistic view of human nature, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau or John Locke, might also question the significance of the Tongan boys’ story in challenging their theories. Rousseau, for instance, believed that civilization corrupts individuals and that true human goodness lies in their natural state. He might argue that the boys’ cooperative behavior was a result of their isolation from the corrupting influences of society rather than a reflection of inherent human nature.